In early 2025, Thailand became one of a few middle-income countries to legally recognize same-sex marriage.

To better understand one dimension of attitudes toward homosexuality in places like Thailand, Pew Research Center asked people in 15 middle-income countries how they would feel in a hypothetical scenario where they had a child who came out as gay or lesbian. The survey was conducted Jan. 5-May 22, 2024, among more than 18,000 adults. We asked all adults about this scenario, regardless of whether they have children.

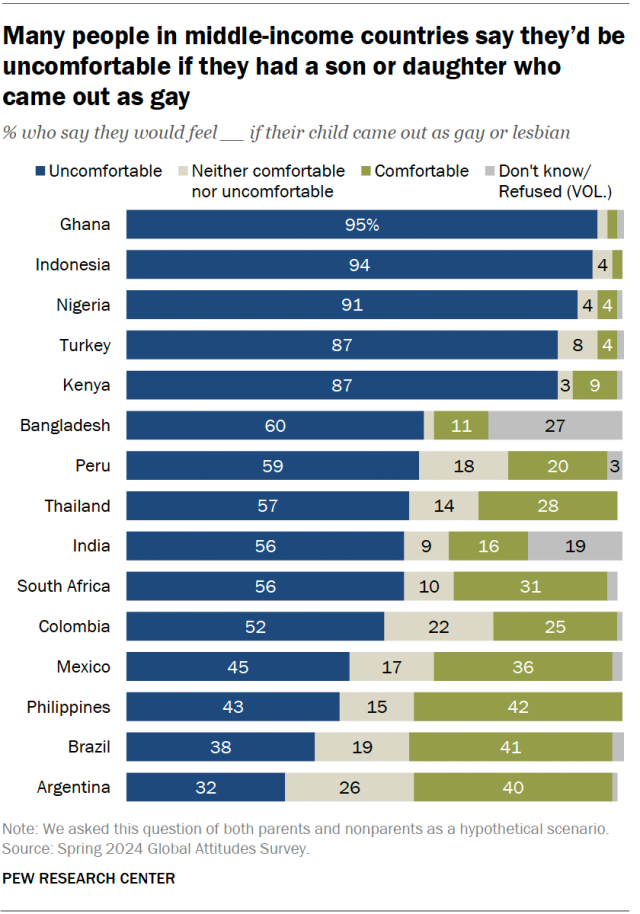

On balance, people in middle-income countries are more likely to say they would be uncomfortable than comfortable if they had a child who came out as gay or lesbian; however, sizable shares say they would be neither comfortable nor uncomfortable.

Argentina is the only country we surveyed where people are more comfortable than uncomfortable if their child were to come out as gay or lesbian. Four-in-ten Argentines say they would feel comfortable in this hypothetical scenario, and 32% say the opposite.

In some countries people’s answers varied by age, education and religious identity. And views are related to how important religion is in their lives.

We did not ask people why they would be comfortable or uncomfortable with having a gay or lesbian child, so their responses are not necessarily a measure of acceptance or unacceptance of homosexuality. People could be comfortable or uncomfortable with their child coming out for other reasons, such as concerns about their safety.

Attitudes toward having a gay child in middle-income countries

About nine-in-ten or more people in Ghana, Indonesia, Kenya, Nigeria and Turkey say they would feel uncomfortable if they had a child that came out as gay or lesbian. In six additional countries, at least half share this view.

But elsewhere, people are more comfortable with this possible scenario – particularly in the Latin American countries we surveyed. About equal shares of Brazilians say they would be uncomfortable (38%) or comfortable (41%) with a child who is gay or lesbian. Another 19% say they would be neither comfortable nor uncomfortable.

How views differ across countries where gay marriage is legal or homosexuality is criminalized

On average, people’s comfort with potentially having a gay son or daughter is higher in countries where same-sex marriage is legal – Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, South Africa and Thailand. The Philippines stands out: There, gay marriage is not legal, but 42% of Filipino adults say they would be comfortable with a hypothetical gay child. Another 43% say they would be uncomfortable.

On the other hand, discomfort tends to be higher where homosexuality is explicitly criminalized, as is the case in Bangladesh, Ghana, Indonesia, Kenya and Nigeria. In each of these countries, six-in-ten or more say they would be uncomfortable if their child came out as gay or lesbian.

Views by age

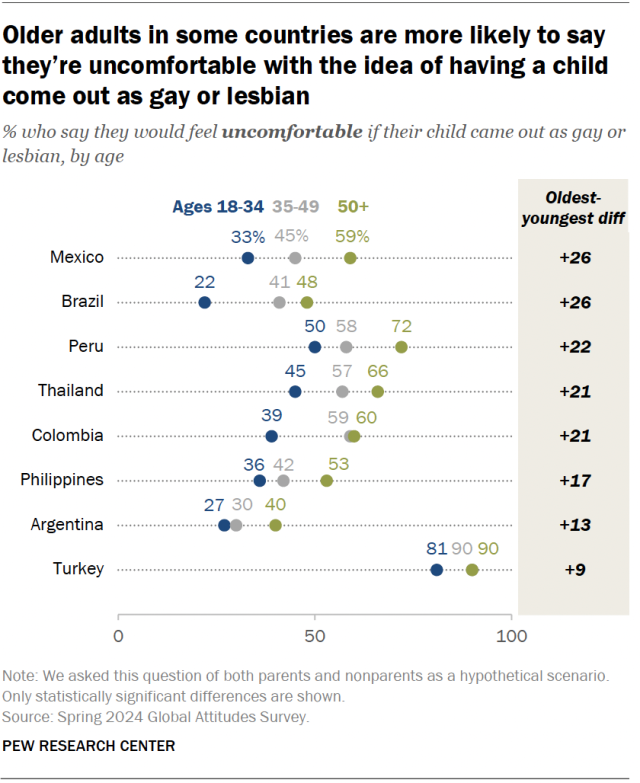

In eight of the 15 countries surveyed, older adults are more likely than younger adults to say that, if they had a child that came out as gay or lesbian, they would feel uncomfortable.

For example, 59% of Mexicans ages 50 or older say they would be uncomfortable with a hypothetical gay child, compared with 33% of those ages 18 to 34.

Similarly, the share of Brazilians 50 and older who say they’d be uncomfortable with a hypothetical gay child is more than double the share of Brazilians ages 18 to 34 who say this.

Views by education

In about half of the countries we surveyed, those with less education are more likely than those with more education to say they would be uncomfortable if they had a child who came out.

People with less education are more likely to say this especially in Latin American countries: Mexico (+26 percentage points), Colombia (+22), Brazil (+18), Argentina (+17) and Peru (+17). Outside of Latin America, views diverge similarly in the Philippines, South Africa, Thailand and Turkey.

In Bangladesh, Kenya and India, we see the opposite pattern. But Bangladeshis and Indians with less education are also less likely than those with more education to answer the question.

Views by religiousness and religious identity

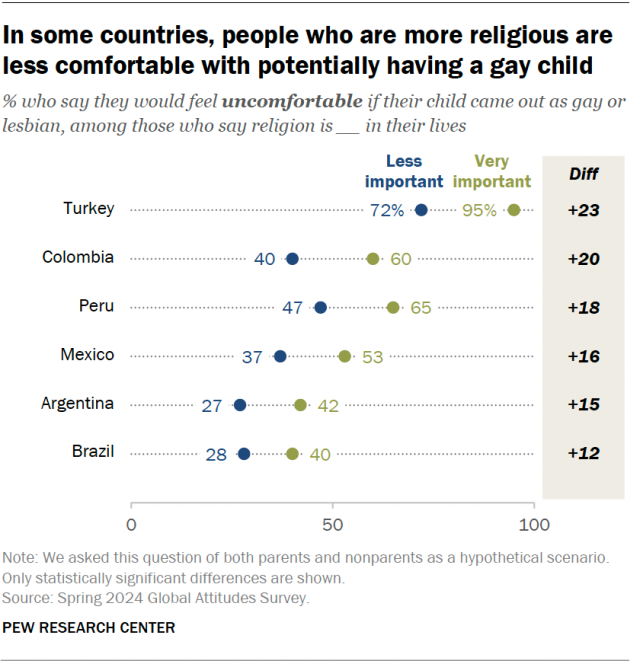

In six of the countries surveyed, people who say religion is very important in their lives are more likely than those who are less religious to express discomfort with the possibility of their child coming out as gay or lesbian.

Consider Turkey: 95% of Turks who say religion is very important say they would be uncomfortable with this, compared with 72% of Turks for whom religion is less important.

Additionally, views differ by 10 or more percentage points in all the Latin American countries surveyed.

This pattern persists even after statistically controlling for people’s ages and levels of education.

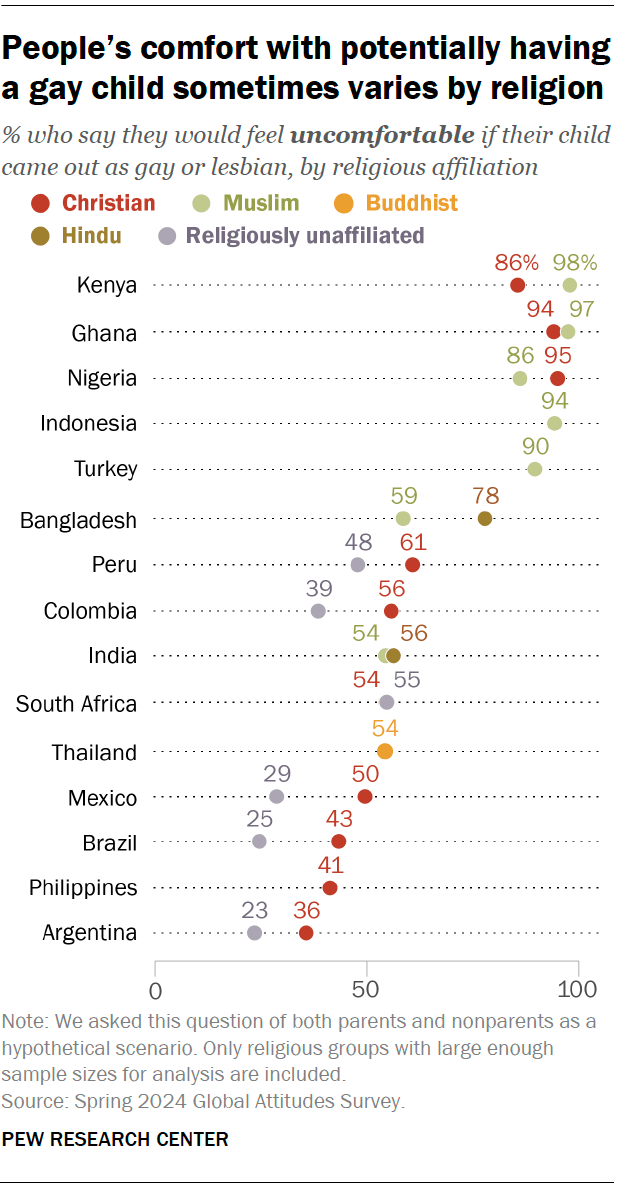

There are also some differences by religious identification.

In sub-Saharan Africa, there is no consistent pattern. In Kenya, a larger share of Muslims than Christians say they would be uncomfortable in the theoretical scenario in which their child came out. The opposite is true in Nigeria. In Ghana, more than nine-in-ten Christians and Muslims say they would be uncomfortable. And in South Africa, over half of Christians and those who are religiously unaffiliated say the same.

In Southeast Asia, Bangladeshi Hindus are more likely than Bangladeshi Muslims to say they would be uncomfortable. But in India, Muslims and Hindus are about equally likely to say this. In both countries, Muslims are less likely than Hindus to answer the question.

Across Latin America, Christians tend to be more likely than those who are religiously unaffiliated to say they would be uncomfortable with their child coming out. But there is also variation among Christians in these countries. Protestants tend to be more likely than Catholics to express discomfort with the possibility of their child coming out.

Note: Here are the questions used for this analysis, along with responses, and the survey methodology.