President Donald Trump and the Republican-led Congress have implemented several major policy changes in the first seven months of 2025. Those changes include raising tariffs on dozens of U.S. trading partners, extending Trump’s first-term tax cuts and adding new ones, and boosting spending on border security and immigration enforcement. Lawmakers have partially offset the tax cuts and spending increases by cutting Medicaid, foreign aid, education grants and other federal programs.

Many analysts project that these policies will further widen the U.S. budget deficit – the gap between how much the federal government takes in and how much it spends. Even before the policy changes, a majority of Americans saw the federal budget deficit as a “very big problem” for the country today, according to a Pew Research Center survey conducted in January and February.

Deficits have to be funded by borrowing, which, for the federal government, means selling bonds to investors. Those investors then resell and trade those bonds in what’s generally referred to as the “bond market.” How the bond market reacts to the administration’s actions not only determines how much interest the government must pay to borrow money; it also influences how much interest ordinary Americans will pay on car loans, mortgages and credit card bills. That’s because interest rates on all sorts of loans tend to move in the same direction.

Here are some basics about bonds and the bond market, using data from the U.S. Treasury and from the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association (SIFMA), a trade group for banks, securities firms and asset managers.

What’s a bond?

A bond is basically a promise to repay a specified sum of money according to rules (interest rate, timing, etc.) that are set when the bond is issued. It’s an alternative to borrowing money from a bank or other financial institution. Governments can borrow from banks, too – especially institutions like the World Bank or the International Monetary Fund – but more commonly they’ll sell bonds to investors when they need extra money.

Bonds are often referred to as “fixed-income” investments because they typically pay interest on a specified schedule – for instance, 5% a year for 10 years, payable semiannually. Those predictable payments can make bonds attractive to a wide range of investors.

Many types of public and private entities can issue bonds, including national governments; states, cities and counties; school districts and other specialized districts; and companies. But since this analysis is about U.S. government bonds, from here on we’ll use “bonds” to refer specifically to those. (They’re also called Treasurys or T-bonds, because the U.S. Treasury Department issues them. The Treasury also sells shorter-term instruments called bills and notes, but for simplicity we’ll refer to them all as bonds.)

How are bonds bought and sold?

The Treasury raises money by selling bonds at regularly scheduled public auctions. At those auctions, individual and institutional investors can specify how much debt they want to buy (with a $100 minimum) and the return they’re looking for.

An investor who buys, say, a 10-year Treasury bond for $10,000, always has the option of hanging onto it. They can collect a decade’s worth of interest payments before the bond “matures” and they get back their original $10,000.

But bonds can also be traded on financial markets, much like stocks. Tradable bonds are also referred to as “debt securities.” Investors can buy and sell bonds at any time before they mature.

Most Treasury debt (about 78.5%, or $29 trillion as of July 2025) is tradable. Treasury securities that aren’t tradable include U.S. savings bonds and the special bonds held by the Social Security and Medicare trust funds.

However, the bond market is much more opaque than the stock market. There’s no physical building or centralized electronic exchange where trading takes place, with prices quoted publicly and in real time. Most of the time, bonds are traded “over the counter” – that is, between private firms called broker-dealers, acting either on behalf of their clients or for their own accounts.

The original issuers don’t directly benefit from trading activity in the bond market. But how an issuer’s bonds fare in the market can influence how much it may have to pay if (or when) it comes back to borrow more.

Related: Key facts about the U.S. national debt

What’s a bond worth?

Investors’ willingness to buy government bonds, and the price they are willing to pay, depends largely on how risky they consider the bonds and whether they can make more money elsewhere. Investors consider many factors when gauging a bond’s value. Some factors involve the general economic and financial climate, such as:

- The strength of the overall economy

- Anticipated future inflation

- The rates of return available from other investments

Other factors are specific to the governmental entity that issued the bond, such as its:

- Total debt load, spending habits and general fiscal management

- Ability (and willingness) to raise taxes to make the interest payments on time

- Political stability

All this matters because bond prices, like stock prices, can move up or down. And that changes the bond’s yield, or the effective return investors get.

When a bond’s price falls, its yield rises; if the price rises, the yield goes down. That’s because, when the price goes down, investors are getting the original interest payments at a discount. When it goes up, they’re paying a premium. (Yield is determined by a rather complicated formula; the following example is somewhat simplified.)

Let’s say the federal government issues $10 million in new bonds to cover some of its deficit. Each bond pays 5% interest annually (half every six months), and they start trading in the bond market as soon as they’re issued.

If traders think the bonds are good investments, they may bid the price up – paying, say, $110 for a bond with a face value of $100. The yield on that bond falls from 5% to 3.79%.

But if traders get worried that the government’s debt load is becoming unsustainable, or that higher inflation may erode the value of their interest payments, they may be only willing to pay $90 for a $100 bond. In that case, the yield rises, to 6.37%.

In general, the more risk investors perceive, the higher return they’ll expect on their investment. And if investors can get a 6.37% yield on existing government bonds by buying them at a discount, the government will have to offer an interest rate close to that the next time it wants to sell new bonds.

How big is the bond market?

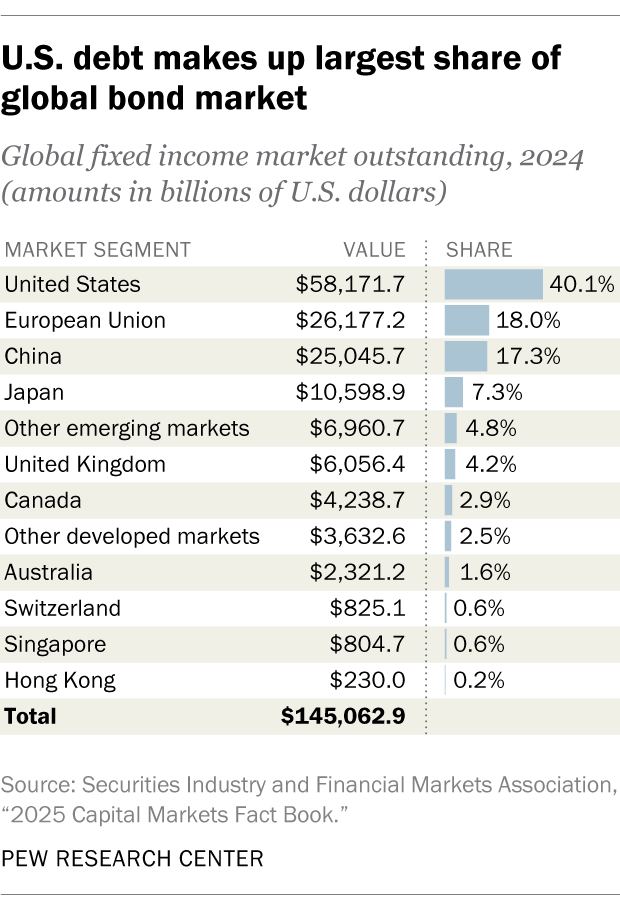

The worldwide market for fixed-income securities of all types totaled $145.1 trillion in 2024 – bigger than the global stock market, according to SIFMA. The U.S. fixed-income market is the world’s largest at $58.2 trillion, or 40.1% of the total. (That figure includes all types of debt securities from both public- and private-sector issuers.)

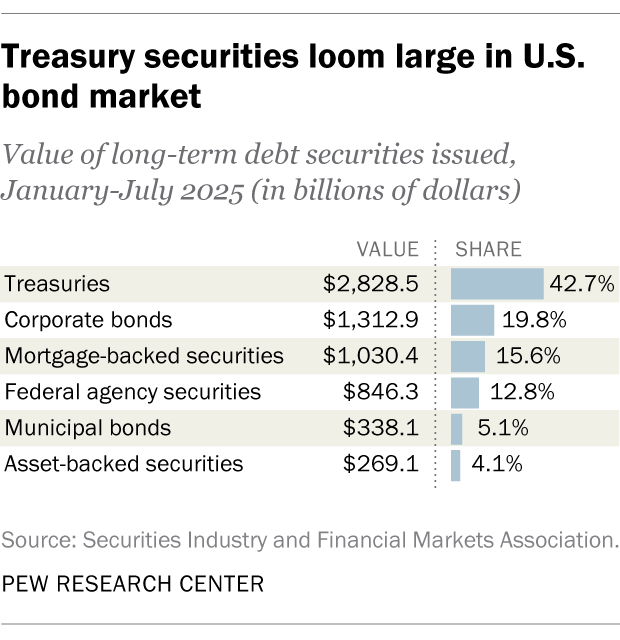

U.S. government securities, in turn, are the biggest piece of the overall U.S. bond market. In the first quarter of 2025, $28.6 trillion worth of Treasurys were outstanding, more than twice the amount of corporate bonds. Treasurys accounted for 60.3% of all U.S. debt securities (excluding mortgage- and asset-backed securities), up from 47.6% a decade ago.

How can the bond market influence government policy?

The federal government borrows a lot of money – both to refinance older debt as it comes due and to fund new spending. Last year, it issued $4.67 trillion in Treasury securities, or about 45% of all new debt in the U.S., according to SIFMA. Through July of this year, the government had issued more than $2.8 trillion in Treasurys.

The government also borrows frequently. The shortest-term securities, called Treasury bills or T-bills, are auctioned as often as weekly, while longer-term bonds are sold monthly or quarterly. That means the Treasury is constantly getting feedback from bond traders about how they view the economy and the government’s actions.

One example occurred in April, shortly after Trump announced sweeping tariff increases on most U.S. trading partners. Treasury yields rose sharply, suggesting that investors were selling off government bonds. Within days, Trump paused many of the steepest tariffs, noting that the bond markets “were getting a little queasy.”

When higher yields in the bond market force the government to pay higher interest rates on newly issued debt, that means more tax dollars have to go to interest payments – instead of, say, the Pentagon, education, public health or disaster relief.

In fiscal 2024, the government’s interest payments on Treasury debt securities (after crediting various government trust funds) totaled $879.9 billion, or 13% of all outlays that year. For context, that roughly matched what the government spent on defense ($873.5 billion) and Medicare ($874.1 billion).

Different bonds have different interest rates, depending on when they were issued and how long their terms are. But the average interest rate on all U.S. government bonds can indicate the broad trend of the government’s borrowing costs.

In July, the average rate on all interest-bearing Treasury debt was 3.352%, according to Treasury Department data. That’s still well below decades past – for example, the average rate was nearly 9% in 1989 and nearly 6.6% in January 2001. But it’s the highest average rate since October 2009, and more than double the most recent low (1.556% in January 2022).

In May, Moody’s – one of the three major debt-rating firms that help investors gauge how risky bonds are – cut its grade on U.S. government debt, saying it believed “persistent, large fiscal deficits will drive the government’s debt and interest burden higher.” It was the last major rating agency to do so.