Trust in the government and the people running it is low, and many Americans think this lack of trust is a serious problem for the country. Two-thirds of Americans perceive that the public has low confidence in the federal government, and three-quarters believe – correctly, according to polling that dates back to the late 1950s – that confidence has been shrinking over time. About four-in-ten say the public’s level of confidence in the federal government is a very big problem, and a similar share thinks it’s a moderately big problem. Although the public’s confidence in the federal government does not rank particularly high on a list of problems facing the country, nearly two-thirds of those interviewed say that the public’s low level of trust in the federal government makes it harder to solve many of the country’s problems.

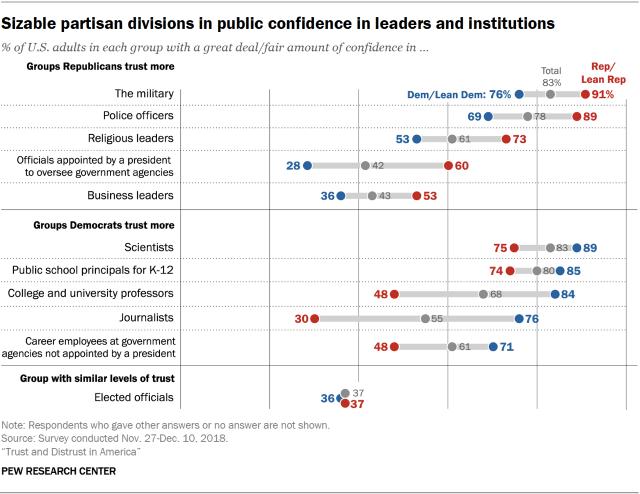

Just 37% say they have at least a fair amount of confidence in elected officials to act in the best interests of the public; 63% have “not too much” or “no confidence at all.” But looking beyond elected officials, trust in other major institutions and leaders is greater. Majorities of the public say they have at least “a fair amount” of confidence in the military, scientists, public school principals, police officers, college and university professors, religious leaders and journalists.

Even with respect to the federal government, people’s judgments depend on exactly which federal officials they are asked about, suggesting that views are highly nuanced. When asked about their level of confidence in officials appointed by the president to oversee government agencies, only 42% of adults register at least “a fair amount” of confidence, and responses are strongly related to party affiliation. But when asked about career government agency employees who are not appointed by the president, about six-in-ten (61%) say they have at least a fair amount of confidence in these individuals to act in the best interests of the public. Partisanship colors these opinions as well, but not as much as with political appointees. Democrats are more likely than Republicans to say they have confidence in career employees; Republicans are more likely than Democrats to say they have confidence in political appointees.

Most people (57%) think public confidence in the federal government has declined in recent years and don’t think the government deserves more public confidence than it gets. Yet, perhaps signaling that people think confidence needs to be higher, a similar share (62%) believes that the public has too little confidence in the federal government.

Confidence in leaders and major institutions is mixed

The public is not skeptical about all institutions and leaders. In fact, most people have positive views about most of the groups asked about in this survey. More than eight-in-ten Americans (83%) say they have at least a fair amount of confidence in scientists to act in the best interests of the public, and the same percentage say this about the military. Nearly as many express confidence in school principals and police. College and university professors are viewed with confidence by 68% of those surveyed; 61% say they have at least a fair amount of confidence in religious leaders to act in the best interests of the public.

Opinion about journalists is more mixed. A small majority of the public (55%) reports having at least a fair amount of confidence in journalists. By contrast, two groups receive confidence ratings that are negative, on balance. About four-in-ten (43%) say they have at least a fair amount of confidence in business leaders, while an equal share has not too much confidence and 14% say they have no confidence in business leaders. Elected officials are at the bottom of the list, with 37% expressing at least a fair amount of confidence; 48% say they have not too much confidence and 15% express no confidence in elected officials to act in the public’s best interests.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, partisanship shapes confidence in many of these institutions and leaders. But views of elected officials in general are remarkably similar across party lines: 37% of Republicans and the independents who lean Republican, compared with 36% of Democrats and Democratic leaners, express at least some confidence in elected officials. Those who identify with a party – whether Republican or Democrat – tend to be somewhat more positive than those who just lean toward a party.

Partisan differences range from 11 to 46 percentage points for all of the other institutions and leaders in the list. Views are most sharply partisan for journalists (a 46-point gap, with 30% of Republicans and 76% of Democrats expressing at least a fair amount of confidence), college professors (36-point gap, again with Republicans less favorable), and presidential appointees to executive agencies (32-point gap, this time with Republicans more favorable). Partisan gaps are quite sizable for career agency officials (23-point gap, with Democrats more favorable), religious leaders and the police (20 points, with Republicans more positive than Democrats for both groups) and business leaders (17 points, with the same partisan pattern).

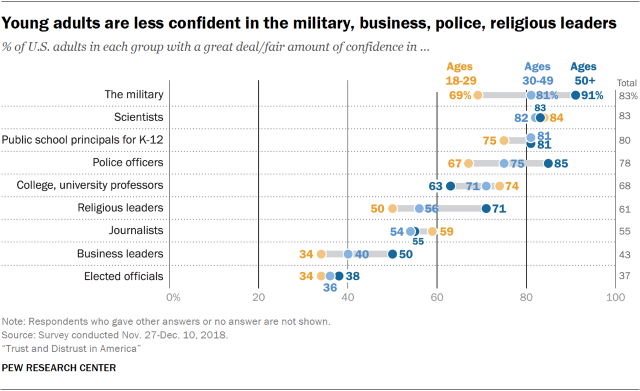

Younger adults tend to express less confidence in several of these leaders and groups than do older adults. Adults under 30 are significantly less confident about the military, religious leaders, business leaders and police officers than are those 50 and older. This pattern is especially evident among Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents. Among different age cohorts of Republicans, the pattern is more mixed.

Racial and ethnic differences in confidence tend to be fairly modest except in regard to journalists and the police. Blacks express much more confidence in journalists – but much less confidence in police officers – than do non-Hispanic whites. Blacks are more likely than whites to have at least a fair amount of confidence in university professors (80% vs. 64%). And among blacks in the survey, about half (52%) say they have either a fair amount (39%) or a great deal (14%) of confidence in police officers. By comparison, 85% of non-Hispanic whites express at least a fair amount of confidence in police officers, including 36% who say they have a great deal of confidence in them.

In sum, there is no generalized propensity to trust leaders. The level of trust people express depends on both who is being asked and who they are asked about. In broad strokes, similar individuals tend to trust presidential appointees, police officers, the military, religious leaders and business leaders; they express less trust in other groups they are asked about. At the same time, others tend to trust career civil servants, scientists, college and university professors, journalists, and public-school principals.

A bipartisan opinion: Confidence in the federal government has been declining

If there is a consensus view when it comes to the issue of the public’s trust and confidence in the government and in each other, it is that trust in government has been declining. Three-quarters (76%) say trust in the federal government is lower now than it was 20 years ago, while only 6% say it is higher; 17% say it’s about the same.

There is little difference between Democrats (79%) and Republicans (74%) in the view that there is less confidence in the government today. Sizable majorities of all racial and ethnic groups agree, though whites are particularly likely to feel that.

Younger adults are somewhat less likely to share this opinion, compared with older adults. But even among younger respondents, roughly two-thirds agree (69% among those under 30 vs. 84% among those 65 and older).

Public sees confidence in the federal government as a lower-tier problem

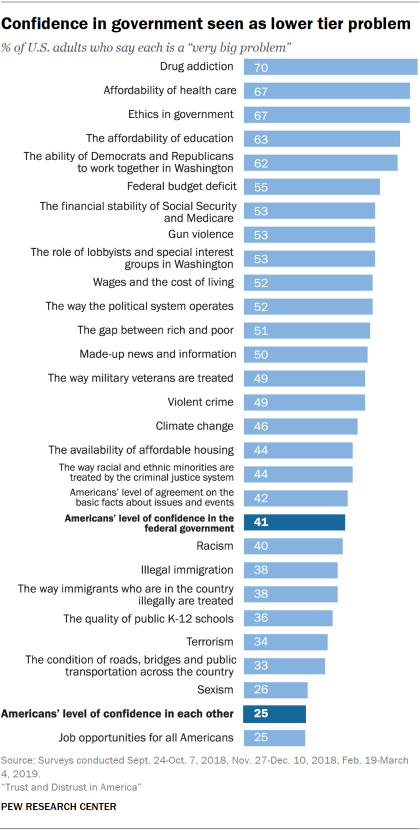

Trust in the federal government and the people running it is clearly quite low among much of the public, and most Americans are aware that the public lacks confidence in its leadership. But is a lack of public trust itself perceived as a problem for the country? Compared with a variety of other public problems, lack of confidence in the government registers as a problem but ranks lower than notable numbers of the issues asked about. Especially when compared with substantive issues like health care, drug addiction and the affordability of education, lack of public confidence is government is seen by considerably fewer people as a very big problem (41%, compared with 67% saying this about the affordability of health care, 70% about drug addiction and 63% about the affordability of education).

But other process issues that are likely related to public trust in government are viewed as serious problems by sizable numbers of people. The issue of ethics in government is viewed as a serious problem by about as many people (67%) as drug addiction – the top issue, at 70%. And 62% say the ability of Democrats and Republicans in Washington to work together is a very big problem. About half identify “the way the political system operates” (52%) and the role of lobbyists and special interest groups in Washington (53%) as very serious problems.

Of comparable concern to confidence in the federal government was Americans’ level of agreement on the basic facts about issues and events (42%). Even though the vast majority of those surveyed (71%) said they thought Americans as a whole have become less confident in each other over the past two decades, just 25% identify Americans’ level of confidence in each other as a very big problem.

Although only a minority of the public identifies confidence in the federal government as a serious problem for the country, the share that does so is comparable to the number who identify the availability of affordable housing and illegal immigration as very big problems. And several perennial political issues are viewed as less serious than public confidence in the government, including the quality of public schools (36% say it’s a very big problem), terrorism (34%), the condition of roads, bridges and public transportation across the country (33%), sexism (26%) and job opportunities (25%).

Democrats are more likely than Republicans to view the current level of public confidence in the federal government as a big problem. Among Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents, 47% say this, while 34% of Republicans and Republican leaners do so. In general, larger shares of Democrats than Republicans find the issues asked about to be big problems, though for many items the size of the partisan gap is relatively modest. There is little difference in perceptions of Democrats and Republicans about the extent to which the financial stability of Social Security and Medicare is a problem; there is also little partisan difference in views about the way military veterans are treated. And, notably, there is bipartisan agreement in the view that the ability of Democrats and Republicans to work together in Washington is a very big problem; 65% of Republicans say this, as do 62% of Democrats.

In general, smaller shares of younger adults express concern about many of these issues, compared with older people. For instance, a far larger share of older than younger adults perceive the role of lobbyists and special interests as a very big problem. About seven-in-ten adults 65 and older say this (71%), compared with just 36% among those under age 30. Similarly, the ability of Democrats and Republicans to work together is viewed as problematic by 73% of those 65 and older but only 47% of those under 30. Similar but less striking differences by age are seen with respect to Americans’ level of confidence in the federal government, the condition of the country’s infrastructure, the way military veterans are treated and the financial stability of Social Security and Medicare.

Young and old generally agree about the seriousness of some of these issues: There is little difference by age in views about the quality of the public schools, Americans’ level of agreement on basic facts and the availability of affordable housing. Young people are somewhat more likely than their elders to view Americans’ level of confidence in each other as a very big problem. But even among those under 30, just 31% do so.

In their own words: Americans cite a range of causes and consequences of low trust in government

To better gauge the public’s thinking on these and other issues raised in the survey, groups of respondents were asked to describe, in their own words, their reasoning and concerns about various topics related to trust. To minimize the burden on any given participant in the survey, smaller groups of respondents were chosen at random to offer these open-ended responses. And offer they did.

Large majorities of those asked to respond provided at least a brief explanation to most questions, and many provided very extensive and detailed answers. For example, asked why the public is now less confident in the government than it was 20 years ago, the roughly 3,400 respondents who answered wrote nearly 75,000 words in total. These responses were read, coded and classified and will be described in this chapter and throughout this report. A selection of the responses will be included, sometimes lightly edited for punctuation, spelling and clarity, to convey some of the passion and concern expressed by the respondents.

Why is there less confidence in the federal government today than 20 years ago?

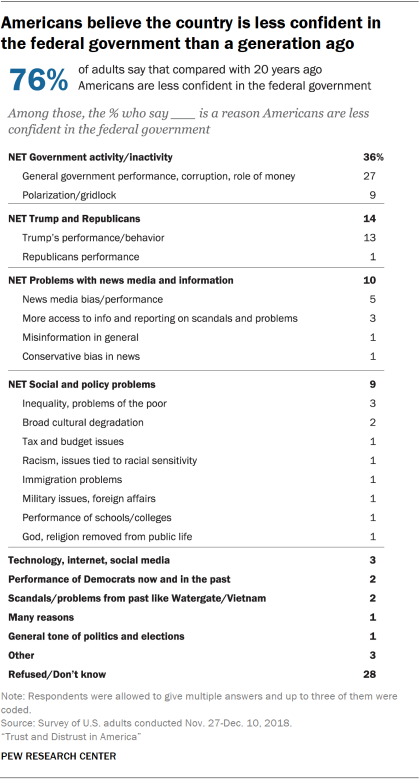

The survey’s respondents who said that confidence in the federal government has declined over the past 20 years had a lot to say about why this has happened. While about three-in-ten declined to answer, those who did provided responses that ranged widely, touching on government performance, the behavior of the president and the parties, the intractability of problems, and polarization among the public and its leaders.

The most common responses dealt with government performance or lack thereof. Overall, 36% wrote something related to how the government is performing – whether it is doing too much, too little, the wrong things or nothing at all – how money has corrupted it, how corporations control it and general references to “the swamp.” While Republicans (at 41%) are more likely than Democrats (32%) to talk about government performance as a reason for the decline in trust, this is a relatively bipartisan view. And Democrats and Republicans are about equally likely to refer to polarization and gridlock as sources of public discontent (9% and 11% each, respectively).

[Veterans Administration]

The behavior and policies of Donald Trump are mentioned explicitly by 13% of respondents; not surprisingly, this is a theme articulated almost exclusively by Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents (22% vs. 3% by Republicans). Another 1% of respondents mention the Republican Party specifically. Typical of those mentioning the president was this response: “We have a president who thinks he can do or say anything without repercussions and with a God complex. He knows nothing about foreign affairs or diplomacy and lies continuously, contradicting himself regularly. He is scary.”

Another wrote: “Donald Trump has created a government atmosphere of ‘alternative facts’ and made up information with no room for dialogue or truth. This makes it very difficult for sincere government workers to do their jobs and makes it easier for incompetent or unethical government workers to move ahead without any checks and balances. I believe that chaos is not conducive to effective government, and just creates further distrust and lack of confidence that departments are working toward the same goals for America.”

Although far more people mentioned Trump and the Republicans as culpable for the situation, some did call out the Democrats or the left, as this woman did: “I don’t recognize my country. Left wing mobs are out of control; the border is under siege; lack of morals and respect (especially our elected officials); lack of decorum and dignity during public hearings; crooks not being held accountable for their actions: CLINTON.”

Roughly equal shares of respondents mention the news media and information sources (10%) and specific policy and social issues (9%) as reasons for the decline in public trust. These topics are cited in roughly equal numbers by both Democrats and Republicans. One broad comment about the media was provided by a 55-year-old man: “Certain media personalities and companies are providing their listeners and viewers with a biased view of the world and the government. They depict everyone as having a secret agenda that is trying to manipulate the public. The hosts portray themselves as the only trustworthy source of information. The viewers then feel compelled to tune in, because they want ‘the truth.’ In the end it is those same people who are being manipulated….”

Typical of criticism of partisan news sources was this comment: “There are now more sources of targeted news that present propaganda – output intended to mold audience to adherence to a single view and prejudice it against other views – and generally false ideas including lies about the government – both people and structure – and events both here in the USA and worldwide.”

With respect to policy and social issues, respondents named a wide range of problems that they believe the government has not dealt with or has exacerbated. These include inequality and the problems of the poor (3%), cultural degradation (2%), and race, taxes, deficits, immigration, foreign affairs, education and religion (roughly 1% each).

A few other topics are mentioned by numbers of respondents, including the influence of social media (3%), scandals and problems from the past (2%) and the general tone and tenor of politics (1%).

What are the consequences of low levels of trust in the federal government?

How do Americans think about the impact of low public trust in the federal government? The survey took two different approaches to this question. One was to ask a sample of respondents who said that level of confidence in the federal government is a very big problem to explain why they thought this. The other was to pose a direct question about the impact of low trust on the country’s ability to solve problems, and then to ask those who said low trust hinders the country to describe which problems they are thinking about.

Many survey respondents struggled with the more general question of how the level of confidence constitutes a problem for the country. While a large majority of those who characterized the level of trust as a very big problem provided an answer, many of those responses addressed the causes of low trust and the general condition of political polarization rather than the consequences.

But many did focus on how the public’s level of confidence produces gridlock and hinders the country’s ability to deal with its problems. As one respondent put it, “Confidence in the federal government helps the country work well together. We are currently fighting each other.” Another wrote: “There is a lack of bipartisanship in the government. We are not working together to solve problems, rather just pointing fingers at the other party.”

A related theme was that Americans’ trust concerns create a downward spiral that exacerbates the condition. As one respondent put it, “Many people no longer think the federal government can actually be a force for good or change in their lives. This kind of apathy and disengagement will lead to an even worse and less representative government.”

Another theme that emerged is that the public’s presumed lack of confidence can lead to disorder. As one respondent put it, “No trust in government leads to violent protests, anarchy, and seems to bring out the worst in everyone. Increases the voice of conspiracy theorists.”

Another said, “With the current state of the government, there is unrest in the American citizens on what is the primary focus of the government and why. Without confidence in the government it may result in civil unrest which in turn hurts our country as a whole.”

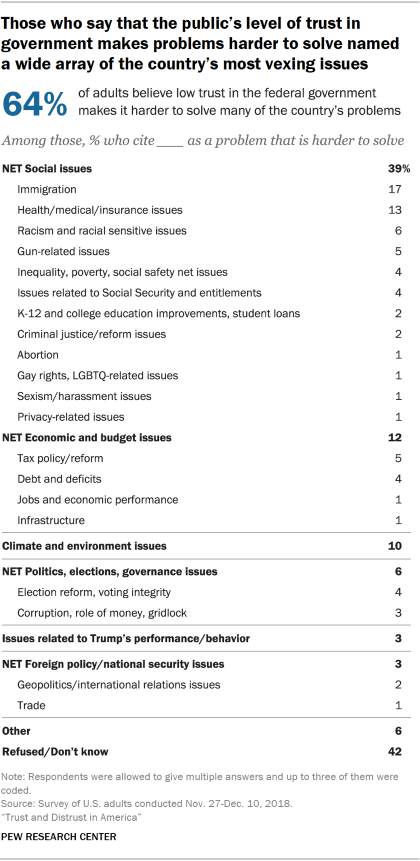

Although only a 41% minority lists the public’s level of confidence in the federal government as a very big problem for the country, a majority endorses the idea that the presumptive low level of trust can have negative consequences. When asked directly whether low trust in government makes it harder to solve many of the country’s problems, nearly two-thirds (64%) say that it does; just 35% say the country’s problems would be just as hard to solve even if trust in the federal government was higher.

Those who said that low trust makes it harder to adequately solve the country’s problems were asked which issues they were thinking of; 60% mentioned at least one issue, with many offering three, four or more examples.

The issues spanned a broad array of topics, with a couple getting more attention getting more attention than others. Immigration – an issue that has defied serious congressional and presidential efforts over the past two decades to resolve – was mentioned by 17% of those asked the question. Slightly fewer (13%) mentioned an issue related to health care or health insurance. Economic topics were cited by a comparable number (12%), encompassing such issues as tax policy, the deficit, jobs and infrastructure. Climate change and the environment followed closely (mentioned by 10% of those asked). Problems with gridlock, elections, corruption, money in politics and other general governance topics were mentioned by 6% of respondents. Explicit mentions of Trump constituted 3% of answers, as did mentions of foreign policy issues including world trade and Russia’s behavior.