If both Obama and Clinton enjoyed success in controlling the master narratives about their campaigns, and McCain less so, how did the public respond? How closely did public opinion about the candidates match up with the major media narratives about the campaigns? And which candidates fared best?

To find out, the Pew Research Center for the People & the Press conducted two surveys testing the narrative messages we found in the press coverage with the public, one in February and April 2008. They asked Democrats and Democratic-leaning Independents which of the two Democratic candidates the public associated more with certain character traits. Republicans and Republican-leaning voters were asked how closely they associated certain traits and characteristics with John McCain. Read full questionnaire.

The results suggest that perceptions of Obama’s candidacy among Democratic and Democratic-leaning voters tracked closely with key media narratives about him.

That was also the case with GOP candidate McCain, whose ratings among the Republican-aligned population largely dovetailed with both his positive and negative themes.

With Clinton, the verdict was more mixed. Some of the views Democrats hold of the New York senator—particularly regarding her honesty and preparation for leadership — appear to be based on factors other than the media narratives, a sign that perhaps perceptions of Clinton were solidified well before the campaign began.

There was another notable difference among the candidates. Despite intense campaign coverage and shifting narratives, voters’ perceptions of Obama and Clinton changed little between February and April 2008. In McCain’s case, public opinion on a range of character and leadership issues improved noticeably, even though the coverage of him personally was not particularly positive. It may be that winning is simply its own reward.

These findings do not imply a simple cause and effect. In some cases, the press may have been reflecting existing public attitudes rather than shaping them. In others, the coverage and the public may have arrived at similar conclusions at similar times. And some public perceptions may simply have pre-dated the campaign. Rather it speaks to the extent that press coverage and public views corresponded to each other during the primary battles.

Obama and Clinton

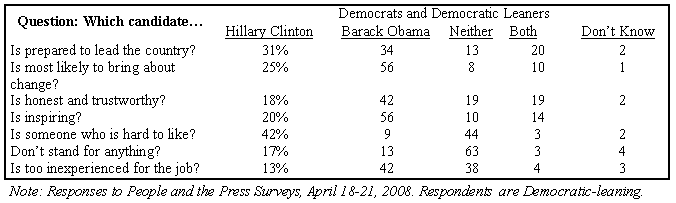

Democrats and Democratic-leaning voters associated Obama over Clinton as “most likely to bring about change” by a ratio of about to 2-1, and that number increased slightly but not dramatically over time. In February, the margin was 52%-26% and it inched up to 56%-25% in April. The voters’ verdict was about the same in a related question—which of the candidates was more inspiring. Respondents again selected Obama by a 54%-20% margin in February and by virtually the same spread (56%-20%) in April.

In both cases, public sentiment closely tracks the most prominent Obama theme of hope and change, and it may well reflect on the most dominant negative theme about Clinton, that she is the candidate of the status quo and the politics of the past.

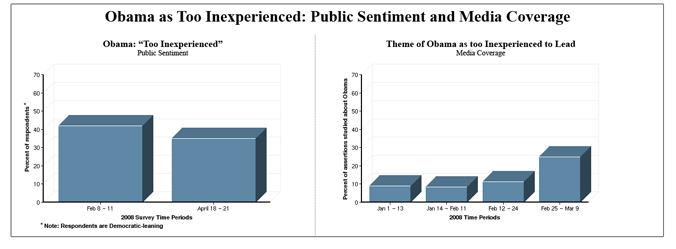

If the public saw Obama as a change agent, they also had growing doubts about his readiness for the presidency, tracking with growing press coverage raising that issue. In February, likely Democratic voters viewed the Illinois senator as too inexperienced for the presidency by a 35% to 18% margin over Clinton. By April, the gap had stretched to 42% to 13%.

Several questions seemed to reflect some disconnect between the public and the media coverage. One had to do with which candidate Democrats saw as more honest and trustworthy. In the two primary season surveys, likely Democratic voters clearly saw Obama as more honest, associating this trait with him over Clinton by a margin of about 2-1. Yet in the press coverage, honesty was not an attribute particularly associated much with either candidate. For Obama, indeed, rebuttals about the idea that he is honest and has integrity exceeded the assertions. The narrative thread about Clinton that connects to this question of trustworthiness, the idea that she lacks core beliefs, was also not a major element in the coverage during the time studied. There also seemed to be some disconnect over the question of likeability. In both the February and April surveys, 42% of the respondents said Clinton was hard to like compared with only 9% who said this about Obama. Yet, in press coverage, Clinton appeared to have waged a successful battle against this impression. In short, while the subject of Clinton’s likeability was a major story, with the media coverage split (22% of all assertions dealt with the issue one way or another, but a majority refuted the idea she was not likeable), a large portion of the public had already decided they had her doubts about her.

Shifts over time

It’s hard to pinpoint when Democratic-leaning voters solidified their views of the candidates, but for the most part, there was little movement between the February and April polls. Opinions persisted despite the sheer intensity of the coverage (the campaign filled 46% of the overall newshole during the weeks studied in the 2008 early primary season).

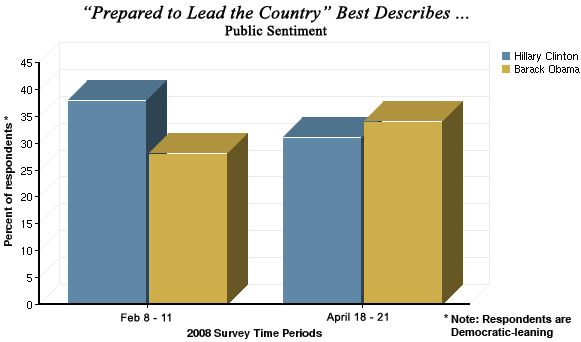

On at least one key question where public perceptions did change, it seemed to be much more closely tied to actual primary results than any media narratives. In the February poll, Clinton held a 10-point lead (38%-28%) when voters were asked who was more prepared to lead the country. But by April, Obama had inched ahead on the question by a margin 34% to 31%. (This despite the fact that respondents in both polls overwhelmingly named Obama as the Democrat who was too inexperienced for the job.)

Yet the message that Clinton was prepared to lead on Day One was the most prominent thread in the coverage about her, and it gained strength as time went on. It originated, however, with the candidate herself. In short, despite the coverage of the idea that Clinton was prepared to lead, Obama gained momentum on this question with the public—and this came in the face of substantial coverage of the Clinton camp’s attacks on his lack of experience. Democrats, in other words, seem to discount Obama’s relative inexperience, or believe he is ready to lead the country anyway, despite C

linton’s emphasis on this issue, and sizable media coverage of it as well.

This sets up a clear question for the fall campaign. Americans have heard a growing chorus of doubts in the media about Obama’s readiness. They are likely to hear more. This has already become a common refrain of the McCain camp, as it was in the Clinton camp. The question is whether that will begin to erode support in a challenge against McCain, or whether Obama’s lack of seasoning is viewed by Americans as simply part of what comes with a candidate who represents a vision something new and different.

John McCain

By and large, there was a solid connection between what the press was saying about John McCain and what the public was thinking about him. Much of McCain’s media narrative improved over time, as the 2007 media primary spilled over into the 2008 voter contests. And by the time the Pew Research Center polled likely Republican voters earlier this year, their view of him on most issues was positive and getting even more positive.

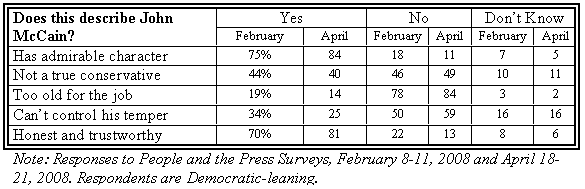

The February and April polls of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents offer a lot of good news for McCain on a series of personal and character issues. But there is one big area of doubt, and it is the same area he has struggled with in the press: The idea that he is not a true conservative. That has been McCain’s dominant media narrative throughout 2007 and in the early part of 2008. And Republicans seem clearly split over this. In the Feb. 8-11 survey, 44% of the respondents agreed with the statement that he is not a true conservative versus 46% who did not. That number only improved marginally, to 40% agreeing and 49% disagreeing, by April. (It is worth noting that the unreliable conservative narrative about McCain did abate in late February and early March.) While slightly more Republicans said it did not describe him, the verdict is clearly still out.

Republican-leaning voters also have come to believe what was in the press coverage about McCain’s character and conviction, the strongest positive theme in the personal narrative about him. That coverage was based largely on assertions from the candidate (27%) but a substantial portion also came from the press (23%). Three-quarters of respondents surveyed in February agreed that the Arizona senator had admirable character, and that number moved up further to 84% in April.

The question of McCain’s age, another issue in the coverage, also began to diminish somewhat over time. In February, just 19% of those likely Republican voters thought McCain is too old for the job. And by April, it had fallen to 14%. That roughly reflects the trajectory of the media narrative that McCain was too old, which was a significant theme in 2007 coverage but had decreased to less than 2% of the 2008 campaign storyline.

Potential McCain voters appeared to have more concerns about the GOP candidate’s temperament, but they too abated as that issue diminished in his 2008 coverage. The percentage of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents who said that he can’t control his temper declined from 34% in February 2008 to 25% in April of that year.

The good news for McCain is that in almost every category, potential voters’ perceptions of him—already quite upbeat—grew more positive between the February and April polls.

It’s also true that key aspects of his media narrative improved over time as a campaign once written off by many journalists came back to capture its party’s nomination.

Mitt Romney

How did personal narratives come into play for Mitt Romney, at one time considered McCain’s chief rival for the GOP nomination but then the first of the final five to drop out?

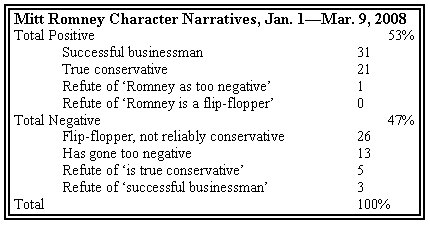

From January 1 through March 9 (Romney dropped out of the race on February 7 and press coverage largely disappeared by late February) the master narrative about Romney was roughly divided. In all, 53% of the assertions studied about Romney personally were positive in nature, while 47% negative.

There were four main master narratives about the former Massachusetts governor. The most prominent of all was a message that the Romney campaign worked hard to project—the image of Romney as a successful businessman. Fully 31% of all assertions studied about Romney were about this theme.

The other master narrative that Romney was trying to project was more mixed in its success. Key to a Romney candidacy was the ability to persuade voters that he was the true conservative candidate—something that would have distinguished him from McCain. And he had some success in projecting this idea. Roughly one-in-five (21%) of the assertions studied carried this theme.

But the notion that Romney was a true conservative was actually more than matched by a negative master narrative about him that undermined this notion. This was the idea that Romney was an unreliable “flip-flopper” on policy positions. In the end, the notion of the opportunistic flip-flopper outshone the notion that he was a true conservative, making up 26% of the assertions studied about him.

One other less-than-flattering master narrative emerged about Romney: the idea that he was too negative in his campaign style (13%).

The Romney campaign had little success refuting the negative master narratives about his opportunism and malicious campaigning tone. And only 1% of all assertions about Romney studied rebutted negative images (5 statements in all).

In short, Romney failed to blunt the strong negative image developing about him in the press, as a flip-flopper who could be nasty in criticizing his rivals.

Romney over Time

Some might imagine that Romney’s master narrative became more troubled as his candidacy lost steam. But that was not the case. Despite an ultimate defeat in the vote, Romney’s presidential hopeful story shows a personal message that grew steadily more positive. What began as a 60-40 tilt to the negative reversed to a roughly 60-40 positive tilt during the time of his withdrawal.

The shift in the tone about Romney was not a case of media remorse once he bowed out. The tone of his narrative message grew most positive in the weeks prior to his departure.

In the first period studied (January 1 – 13), as Romney weathered defeats in both Iowa and New Hampshire, his personal narrative was also battered in the press. Fully 60% of the themes studied about Romney were negative, and the criticism that dominated was Romney’s own negativity. Fully 37% of the assertions focused on Romney’s negative campaigning, spurred largely by a stream of attack ads sponsored by his campaign. During the January 5 debate in New Hampshire, McCain (the subject of most of the attacks) laid into Romney: “You can spend your whole fortune on your ads and it still won’t be true,” and Giuliani commented that even Ronald Reagan would be in one of Romney’s negative attack ads.

In a “Good Morning America” interview on January 3, interviewer Chris Cuomo asked Romney: “You have Ed Rollins from the Huckabee campaign saying he wanted to ‘hit you in the mouth,’ he’s getting so upset at the negative ads. Do you regret a little bit the strategy recently, do you think maybe that’s why you’ve taken a hit in the polls?” Romney coolly answered, “No actually, I’ve been rising in the polls…”

But the Romney campaign had a hard time fending off this image, with rebuttals amounting to just 4% of the assertions about him; by the end of this period, the campaign seemed to be abandoning this tactic. Newsweek’s Howard Fineman, commenting on Romney’s speech on January 8, remarked, “What else was good about Romney tonight is that he was positive… He was the positive, ‘decent as the day is long’ guy that a lot of his friends say he really is, as opposed to the guy whose campaign advisors and consultants are feeding him all these negative lines and negative ads.”

From January 14 through February 3—as Romney pulled in a strong win in Michigan, but then came up short on Super Tuesday—he gained back some control over his personal message. There was a slight tilt toward the positive, 53% to 47% negative.

In these weeks, coverage of Romney’s personal messages grew overall. As it did, his campaign successfully increased his positive personal associations and decreased his negative. The portrayal of Romney as a nasty politician declined dramatically to just 7% of all statements studied while his image as a successful businessman grew to 38%—higher than in any other period.

It was in the final days of his campaign, though, that his personal themes reached most positive levels of all. In the third phase studied, after February 4, the master narrative for Romney personally became more positive. Fully 61% of the assertions were positive in nature. (Romney dropped out during this period, on February 7).

Mike Huckabee

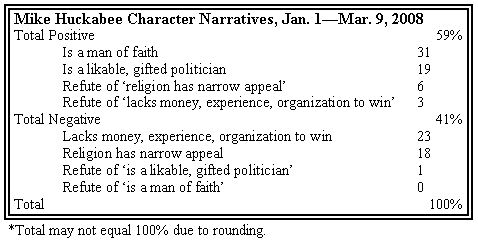

Though less a presence in the press overall, Huckabee’s narrative was also more positive than either of his Republican opponents’: 59% overall, from January 1 through March 9. And, unlike the presumptive nominee John McCain, Huckabee’s positives continually climbed from 48% in early January to 75% by February 17.

In the fourth and final time period of the study—even after Mitt Romney had abandoned his bid for the nomination, McCain had begun efforts to consolidate the party behind him, Huckabee dropped out and George Bush endorsed McCain—Huckabee’s positives still outshone McCain’s by 72% to 51%. Granted, however, the total number of assertions for Huckabee had dropped precipitously by that time.

The most dominant narrative about Huckabee involved his dedication to his religion. Almost a third, 31% of all of assertions studied about Huckabee spoke favorably of his strong religious ties. Another 19% fostered the image of him as a likeable and gifted politician.

The coverage of these two positive narratives about Huckabee had opposing trajectories. Mentions of him as a gifted politician dropped sharply after the first time period (January 1-13, which included his Iowa win). After failing to follow his Iowa victory with other wins, in other, words, the notion that Huckabee had such as skill on the stump began to fade away.

Meanwhile mentions of Huckabee as a man of faith saw steep increases in both the second and third time periods of the study.

Yet not all of the master narratives about Huckabee were positive. The second most prevalent theme in the coverage about him was that he lacked the political wherewithal to actually win. Nearly a quarter (23%) of the assertions about Huckabee studied suggested that his campaign, due to lack of money, experience and organization, could not survive. Many of these statements focused on public missteps and misstatements about Pakistan, Iran, and crossing the picket line during the writer’s strike.

Another 17% of all of the assertions in this study addressed the notion that—while he was otherwise strongly (and positively) identified as a man of faith—his religion might translate into overall narrow political appeal.

Looking at the two religious-based themes together—his strong faith and the sense that his faith might lead to a very narrow appeal, fully 54% of Huckabee’s narrative related in some way to his faith. Starting from a level of 44% of all the threads in the first time period of the study, this percentage climbed to 63% in the second time period, and peaked at 74% in the third time period which included Super Tuesday on February 5.

Even by Super Tuesday, the press had largely discounted Huckabee as a real contender. Over half (54%) of the total assertions recorded for Huckabee during the course of this study occurred in the first two weeks of January—a spate of media coverage coinciding with Huckabee’s victory in the Iowa caucus on January 3. But, in what was perhaps a bad omen for the candidate, the most dominant theme during this time (at 32%) was his lack of experience or money needed to win.