Amid global debates about press freedom, free speech and freedom on the internet, new surveys of 35 countries show there is a disconnect between how people rate the importance of these freedoms and how free they actually feel to express themselves.

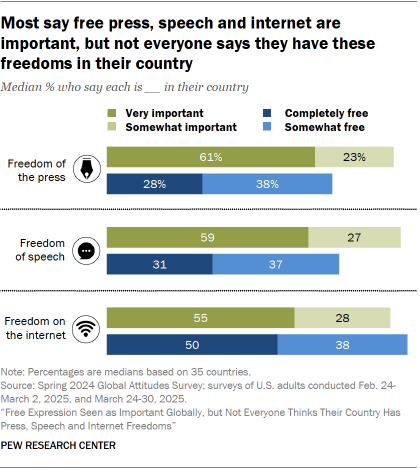

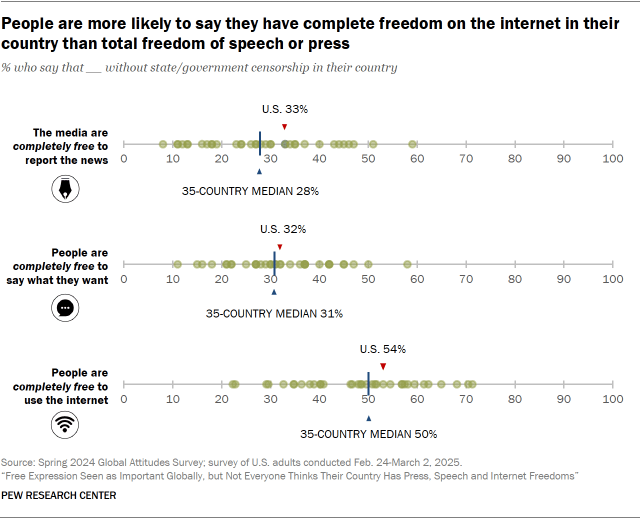

Overall, a median of 61% of adults across 35 countries say having freedom of the press in their country is very important, with another 23% saying it is somewhat important. But only 28% say the media are completely free to report the news in their country, with an additional 38% saying the media are somewhat free.

What is a freedom gap?

We use the term “press freedom gap” to describe the difference between the share of people who say free media without censorship are important to have in their country, and the share who say media in their country are actually free to report the news. Similarly, we use “speech freedom gap” and “internet freedom gap” in reference to questions on those topics.

Similarly, a median of 59% globally say having freedom of speech in their country is very important, while 31% say speech is completely free where they live. This so-called “freedom gap” – where the share of people who value free speech is larger than the share who believe they have it – appears in 31 of the 35 countries surveyed.

On the subject of freedom on the internet, a median of 55% say the ability to use the internet freely is very important, while 50% say they are completely free to use the internet in their country.

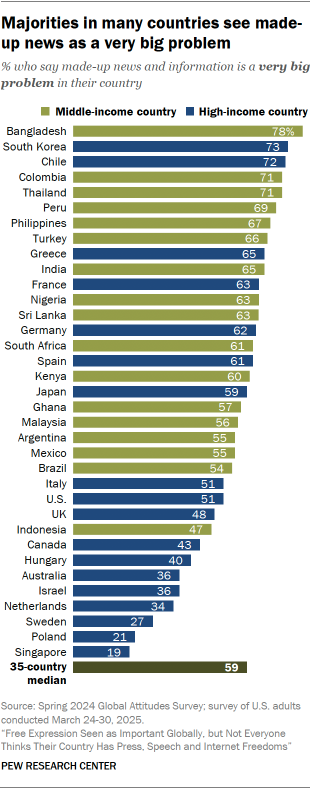

Majorities in over half the nations surveyed also say made-up news and information is a very big problem in their country.

Concerns about fabricated or manipulated news are pervasive across all regions but generally more intense in countries classified as middle-income. Still, majorities see made-up news and information as a very big problem in the high-income countries of South Korea (73%), Chile (72%), Greece (65%), France (63%), Germany (62%), Spain (61%) and Japan (59%).

(We surveyed 17 middle-income countries and 18 high-income countries. Refer to the Appendix for a classification of these nations.)

Furthermore, in every country surveyed except Singapore, a majority of adults say that made-up news and information is at least a moderately big problem.

These perceptions are tied to people’s overall satisfaction with democracy. In many of the countries surveyed, those who express the most concern over made-up news and information are less likely to say they are satisfied with the state of their nation’s democracy.

We mostly observe this pattern in high-income countries like Canada, Greece, Hungary, Israel, Sweden and the United Kingdom – several of which have seen an overall decline in satisfaction with democracy in recent years.

Dissatisfaction with democracy during the 2024 year of global elections

Voters in more than 60 countries went to the polls in 2024. In many of these countries, incumbents lost or suffered major electoral setbacks. Frustration with the way representative democracy is working played a key role in these elections. For more, read our data essay “Global Elections in 2024: What We Learned in a Year of Political Disruption.”

Views of the importance of free speech, free press and internet freedom are also linked with concerns about fabricated news. In many countries, people who say these freedoms are very important are more likely to consider made-up news and information a very big problem where they live. For more, read Chapter 1 of this report.

The rest of this overview explores:

- Views on the importance of free press, free speech and freedom on the internet

- Factors that influence concerns about censorship

- How free people feel they are

- Attitudes on freedom of expression in Latin America and the U.S.

How important are free press, free speech and freedom on the internet?

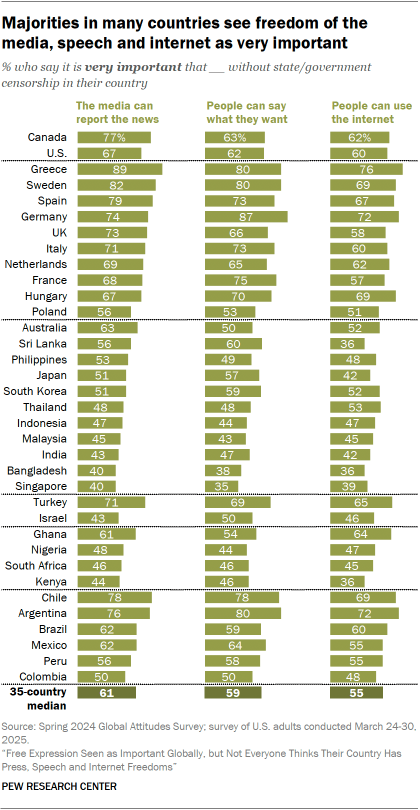

Generally, people around the world believe it’s at least somewhat important that the media can report the news, that people can say what they want, and that people can use the internet without state or government censorship. But there is more regional variation among the shares who see these freedoms as very important.

People in many European and Latin American countries tend to place more importance on these freedoms, while people throughout Asia and sub-Saharan Africa consider them somewhat less important. Of the Middle East-North African populations surveyed, Turks are more likely than Israelis to see these freedoms as very important.

Trends over time

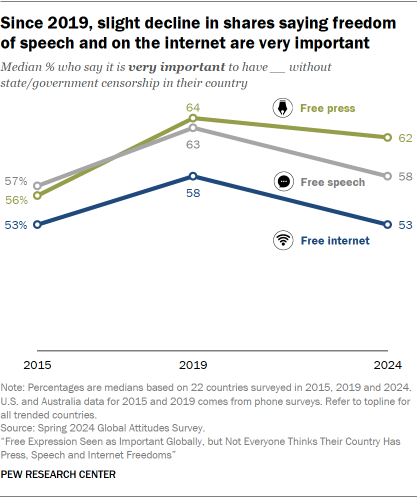

Across 22 countries surveyed in 2015, 2019 and 2024, the median percentage who see freedom of the press as very important is 62% in 2024. This is similar to the 64% median measured in 2019, but up from 56% in 2015. (The 2024 medians were calculated with U.S. data collected in April 2024, though our most recent U.S. data is from March 2025.)

The median percentage who see free speech as very important is 58% in the 2024 survey, down from 63% in 2019.

Similarly, the median share saying freedom on the internet is very important is 53% in 2024, compared with 58% in 2019.

Global attitudes toward both of these freedoms in 2024 are similar to what they were in 2015.

By country

Since 2015, the share of adults saying a free press is very important has increased in Australia, Canada, France, Indonesia, Japan, Italy, Turkey and the UK. The jump in Turkey is especially notable, from 45% in 2015 to 71% in 2024. But in Brazil, Kenya, Nigeria, Peru and South Africa, the share who see freedom of the press as very important has declined since 2015.

In some countries, there have also been changes in views on the importance of free speech and freedom on the internet. For more, read Chapter 2 of this report.

Factors related to concerns about censorship

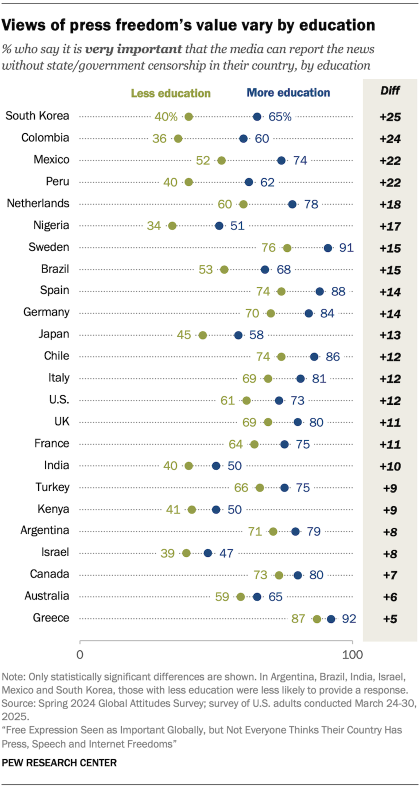

In 24 of the 35 countries surveyed, adults with more education are especially likely to say having media that can report the news without state interference is very important.

Educational differences in views of press freedom are present across various regions, but they are especially large in South Korea, Colombia, Mexico and Peru.

Additionally, attitudes toward freedom on the internet are connected to social media usage, which we measured in 20 primarily middle-income countries. In several of them, social media users are more likely than non-users to believe that the ability to use the internet without censorship is very important.

How free do people feel?

The share of people who say the media are completely free to report the news, that people are completely free to say what they want, or that people are completely free to use the internet varies across the countries surveyed.

But globally, a median of 28% say that the media are completely free where they live, while a median of 31% say that people have complete freedom of speech in their country. Larger shares (50% median) say that people are completely free to use the internet.

In many countries, perceptions of freedom are tied to satisfaction with democracy. Those who think the media in their country are completely free to report the news are more likely than those who say otherwise to approve of the way their democracy is working. The same is true for those who believe that people in their country are completely free to say what they want or to use the internet without government censorship – they rate their democracy more positively than people who say these activities are less free.

Related: What Can Improve Democracy?

Finally, social media users are more likely than non-users to say they have complete freedom on the internet in 12 countries. (We ask about social media use in a total of 20 countries, most of which are middle-income.) For more, read Chapter 3 of this report.

Attitudes on freedom of expression in Latin America and the U.S.

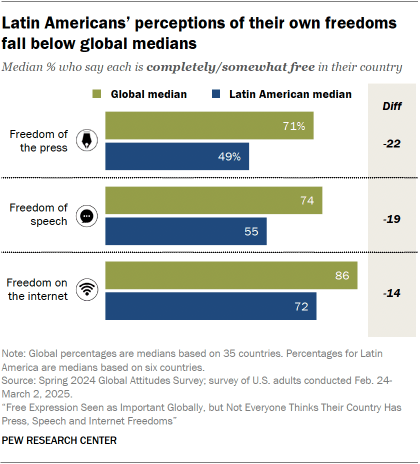

Compared with global medians, Latin American countries have relatively small shares saying their press, speech and use of the internet are completely or somewhat free from censorship.

The difference is especially large on perceptions of press freedom. A median of 49% of adults across the six Latin American countries surveyed (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Peru) say that the press are completely or somewhat free to report the news without censorship in their country. By comparison, a median of 71% say this across all 35 countries surveyed.

In the United States, we asked about freedom of the press, freedom of speech and freedom on the internet as part of our 35-country survey in spring 2024 (fielded in the U.S. in early April). But we asked these same questions again in February and March 2025 to see how Americans’ opinions may have shifted during the second administration of President Donald Trump:

- There has been very little change in Americans’ views of the importance of press freedom. But there has been a slight uptick in the share who say free speech is very important (from 56% in 2024 to 62% this year) and the share who say this about internet freedom (from 54% to 60%).

- When it comes to how free Americans feel they actually are on these measures, more than half (54%) now say people in the U.S. are completely free to use the internet – up from 40% in 2024. Similarly, 32% now say people in the U.S. are completely free to say what they want, up from 28% in 2024. Attitudes on freedom of the press have not changed much overall.

- On all three freedoms – press, speech and internet – there have been considerable partisan shifts since 2024. Republicans have become more likely to see that each is completely free in the U.S., while Democrats have become less likely to say this.

- Overall, Americans’ concerns about made-up news and information are virtually unchanged from 2024. About half (51%) now say made-up news is a very big problem in the U.S. – similar to the share who said this last year.

Related: Americans remain concerned about press freedoms, but partisan views have flipped since 2024

Jump to the following chapters:

Chapter 1: Widespread global public concern about made-up news

Chapter 2: Importance of press freedom, free speech and freedom on the internet

Chapter 3: How people rate press, speech and internet freedoms in their country

Chapter 4: Freedom gaps